New Delhi: Urbanisation has always come with trade-offs. On one hand, it promises speed, choice and access; on the other, it quietly reshapes how—and what—we eat. Today, super-quick access to food through delivery apps and ready-to-eat products makes it easier than ever to skip cooking. A meal is just a tap away. But as cities expand and convenience tightens its grip on our plates, a critical question is emerging: how is it impacting our health?

That question sat at the heart of the India launch of The Lancet Series on Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health, a landmark body of work that brings together years of global evidence to examine how ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are transforming diets—and driving a silent epidemic of chronic disease.

The core problem: displacement of traditional diets

At the centre of the series is a simple but unsettling thesis: ultra-processed foods are displacing traditional dietary patterns across the world—and this displacement is fuelling the pandemic of diet-related chronic diseases.

Explaining the first paper in the series—a collective global effort with over 43 co-authors synthesising evidence built over decades—Dr. Neha Khandpur, Assistant Professor, Division of Human Nutrition & Health, Wageningen University, Netherlands, stated: “The main thesis is around the displacement of traditional dietary patterns by ultra-processed foods.” These foods are not just processed—they are industrial formulations of food substances and additives, engineered for hyper-palatability, convenience and aggressive marketing.

Across regions and cultures, the story is strikingly similar. Water is replaced by sugar-sweetened beverages. Whole yoghurt gives way to flavoured, additive-laden versions. Greens and oats are substituted with ultra-processed breakfast cereals. Freshly cooked meals are replaced by frozen, shelf-ready alternatives.

“It is this substitution—and the health consequences of that substitution—that we attempted to capture,” Dr. Khandpur explained.

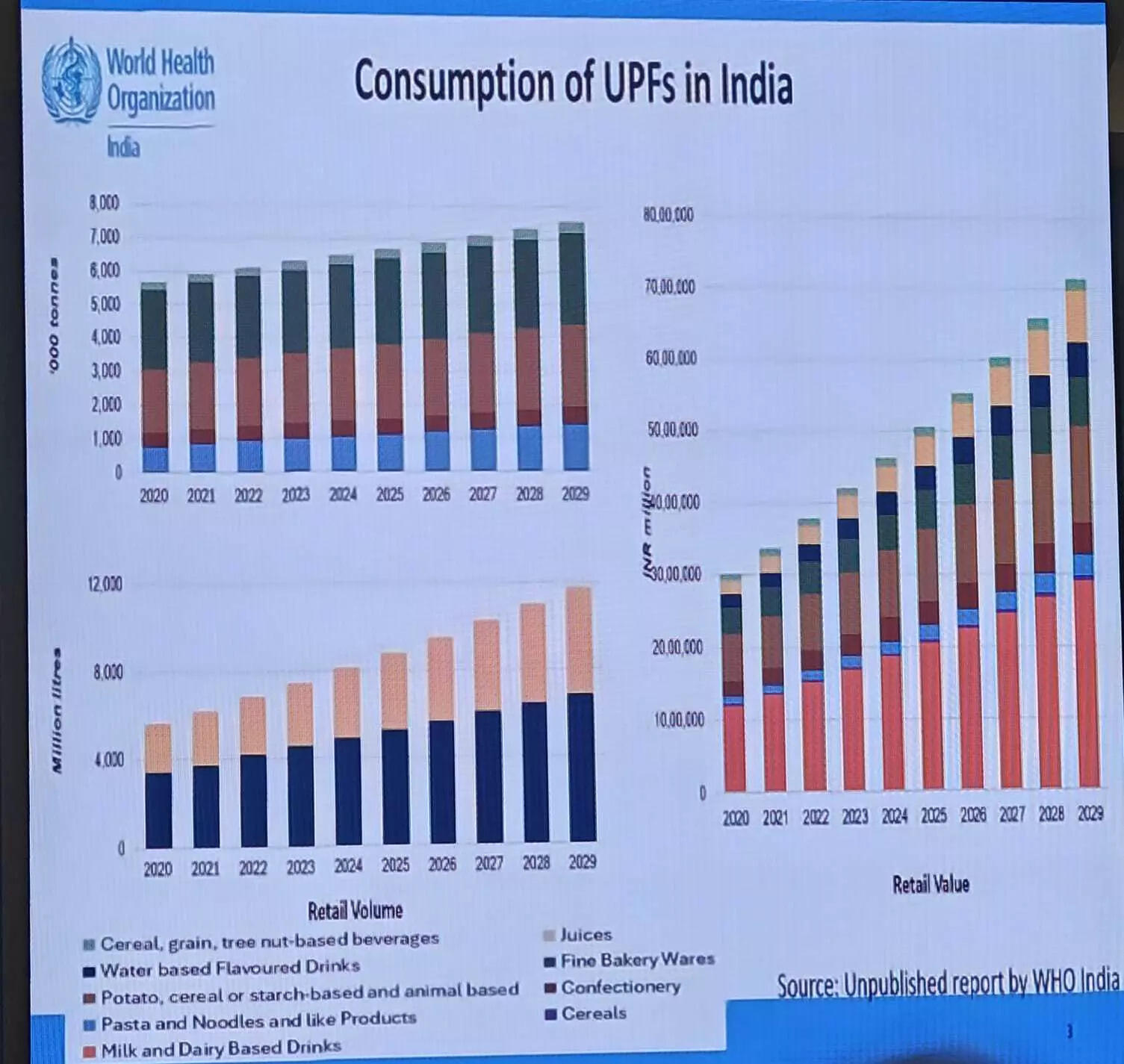

A global surge—especially in low- and middle-income countries

The data paints a worrying picture. Irrespective of region or income level, the proportion of calories coming from ultra-processed foods is rising over time. Using Euromonitor sales data from 93 countries between 2007 and 2022, the researchers found consistent increases in per capita sales of UPFs across low-, lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries.In high-income countries, baseline consumption is already alarmingly high—around 200 kg per capita—and has remained stable, suggesting saturation rather than improvement.

Sugar-sweetened beverages are the biggest drivers of this trend globally, but they are far from alone. Baked goods, sweet desserts, ready-to-eat meals, frozen foods, snacks and even dairy products are rapidly expanding categories. “All of the trends that we’ve been able to capture demonstrate a concerning increase,” Dr. Khandpur said.

Poor diets, predictable outcomes

The Lancet series tested three key hypotheses. The first examined displacement of traditional diets. The second explored whether this displacement worsens diet quality. The third asked whether high consumption of UPFs increases the risk of chronic disease.

The answers were unambiguous.

Across 13 countries—including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, South Korea, Mexico, Portugal, the UK and the US—higher dietary shares of ultra-processed foods tracked closely with increased intake of total fat, saturated fat and added sugars. At the same time, population intakes of fibre, protein and potassium declined.

“These patterns reflect clear nutrient imbalances,” Dr. Khandpur said, “and those imbalances are directly linked to non-communicable diseases.”

Evidence from randomised controlled trials added weight to the findings. Interventions that reduced ultra-processed food intake among people with overweight and obesity resulted in lower total energy intake and significant weight loss—especially when compared with minimally processed dietary patterns.

Chronic diseases: the evidence is hard to ignore

Perhaps the most compelling evidence came from 104 prospective cohort studies tracking people over time. In 92 of these studies, high intake of ultra-processed foods was associated with increased risk across 15 health outcomes—including obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, depression, Crohn’s disease and overall mortality.

“The consistency, strength of association, temporality and biological plausibility make this evidence base very, very compelling,” Dr. Khandpur said. “It is hard to ignore.”

Taken together, the findings confirm what the series set out to test: ultra-processed foods are displacing traditional diets, deteriorating diet quality and increasing the risk of multiple chronic diseases. This displacement, the authors conclude, is a key driver of today’s diet-related disease burden.

Why current policies fall short

While evidence mounts, policy responses remain inadequate. Prof. Mark Lawrence, Professor of Ecological Nutrition, Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), Deakin University, Melbourne, pointed to a critical blind spot in current risk assessment systems.

“Public health protection focuses inordinately on acute food safety risks—important, yes—but says almost nothing about chronic public health risks,” he said. Toxicology and microbiology dominate assessments, while dietary imbalances and long-term exposure to ultra-processed foods are largely ignored.

He cautioned against over-reliance on food reformulation as a policy solution. “A reformulated ultra-processed food is still an ultra-processed food,” he said, noting that replacing one harmful ingredient with another ultra-processed substitute, such as non-nutritive sweeteners, does not solve the underlying problem.

Warning labels, he added, are far more effective than star-rating systems. Evaluations over 12 years show little evidence that rating schemes work; in fact, in Australia, 73% of ultra-processed foods displaying health stars score 2.5 or more out of five—leaving consumers confused rather than informed.

Law, not voluntarism

For Preetu Mishra, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF India, the lesson from public health battles against tobacco, alcohol and breast milk substitutes is clear: enforceable laws change corporate behaviour; voluntary commitments rarely do.

The Lancet series, she noted, explicitly frames ultra-processed foods as a “commercially driven epidemic” and calls for clear legal duties, accountability mechanisms and protection from industry interference.

The concern was echoed by Dr. Arun Gupta, Convener, NAPi, who warned against what he described as the “stakeholder trap”.

“Industry should make money, but not at the cost of people’s health,” he said. Allowing industry to be both a stakeholder and a solution provider, he argued, creates an inherent conflict. “Public health and profit have fundamentally different objectives.”

Dr. Gupta stressed that industry should not be allowed to write the rules by which it is regulated, calling for strong conflict-of-interest prevention frameworks—especially in health and nutrition.

Making it visible to consumers

From a consumer perspective, Ashim Sanyal, CEO, Consumer Voice, highlighted how easy access and misleading advertising are normalising ultra-processed foods, particularly in the Indian subcontinent, where home-cooked meals have traditionally dominated.

Consumers, he said, struggle to distinguish between processed and ultra-processed foods. His organisation has advocated for quarterly trend reports by regulators, publicly naming companies that manipulate consumer behaviour through misleading marketing.

“Restriction must happen at the manufacturing stage itself,” he argued, emphasising that awareness alone is not enough when products are deliberately designed to confuse.

From science to policy: a landmark warning

The India launch of The Lancet Series makes one thing unmistakably clear: the rise of ultra-processed foods is not just a lifestyle issue—it is a structural, commercial and policy-driven crisis. As convenience continues to redefine urban living, the cost is increasingly being paid in chronic disease, stretched health systems and lost years of healthy life.

Prof. K. Srinath Reddy, Chancellor, PHFI, University of Public Health Sciences, said: “These foods disturb and damage the harmony that exists within the body—between the trillions of the microbiome, as well as many other organ systems.” This disruption, he added, leads to severe inflammation that can damage multiple organs.

For Prof. Reddy, the challenge now lies beyond evidence. “Ensuring that food and agriculture policies are geared in such a manner that human health is protected and fostered rather than damaged is the real test,” he noted. Translating credible science into effective public policy, he said, has long been the Achilles’ heel of global nutrition governance. The Lancet series, he added, quietly but powerfully bridges that gap—moving evidence from science to policy.

The science is now unequivocal. The question is the willingness of governments to act on it—before convenience becomes the most expensive ingredient in our diets.