For many Indians, healthcare anxiety does not begin in the clinic. It begins after. A blood test report arrives on WhatsApp. Certain values are highlighted in bold. Numbers fall outside reference ranges. Medical terms sound unfamiliar, and by the time a follow-up appointment is scheduled, the patient has already consulted search engines, relatives, and social media forwards.

This gap between receiving health data and understanding has widened in recent years. Preventive testing has increased, wearable devices like the Apple Watch or fitness apps track daily metrics, whereas chronic conditions such as diabetes and thyroid disorders require constant monitoring through blood glucose interventions. Yet at the same time, consultation time remains limited, and interpretation is often left to patients to navigate on their own.

It is in this space that AI-based health assistants, such as OpenAI’s recently announced ChatGPT Health, are being positioned. Not as diagnostic tools or substitutes for doctors, but as aids that help people make sense of medical information they already have.

When information creates anxiety

According to Dr Akshat Chadha, a Mumbai-based general physician specialising in lifestyle medicine, misunderstanding medical reports is routine rather than exceptional. “Reports are complicated, and the bold values make it even harder. Most patients assume the worst with every abnormal number,” he says.

Prescriptions, too, are often poorly understood. “Medication instructions become confusing once a prescription involves multiple drugs. Among senior citizens, medicines are frequently identified by colour and shape rather than by name.”

This confusion is not anecdotal. A 2024 cross-sectional study titled Use of internet for health information and health seeking behavior among adults by Bhangare, Ashturkar and Giri, published in the International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, found that 82% of 400 adults in western Maharashtra used the internet to look up health information. Nearly half searched for medication-related details such as dosage and side effects, while 45% looked up disease symptoms and diagnosis.

Searching first, asking later

The impulse to search rather than ask is partly behavioral and partly structural. A 2024 cross-sectional survey on Indian physicians titled ‘Doctor-patient communication practices: A cross-sectional survey on Indian physicians’, involving 500 clinicians from Government and private medical colleges, reported a mean consultation time of 9.8 minutes and found that only a portion of doctors routinely encouraged patients to talk about all their health problems in detail. In such settings, patients may leave with instructions but without the confidence or opportunity to clarify what a number might mean, why a medicine was added, or what symptom patterns should prompt a return visit.

This reality helps explain why health-related Internet use and self-interpretation are now commonplace, and why the conversation around AI tools has shifted from diagnosis to preparation.

Interpretation, not diagnosis

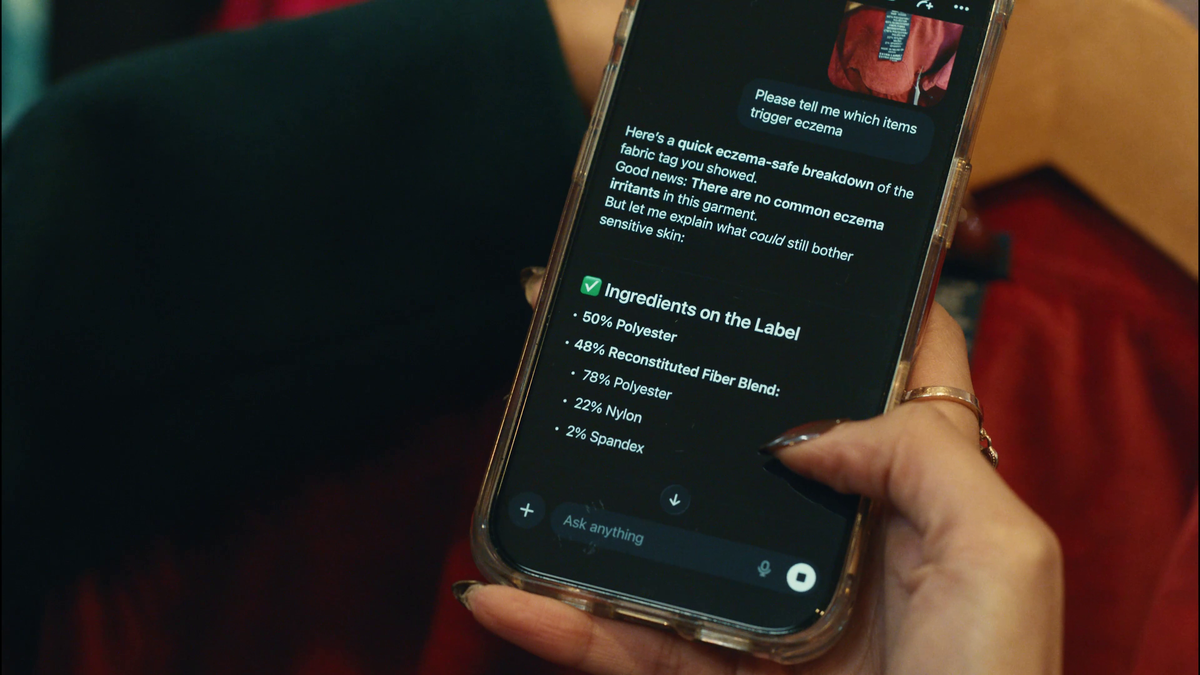

ChatGPT Health is a specialised feature within ChatGPT aimed at helping users make sense of health-related information, not at making clinical decisions. OpenAI stresses that it is designed to assist with interpreting medical reports, prescriptions, and wellness data—optionally linked to a user’s own health and fitness information—rather than offering diagnoses or treatment advice.

Within these limits, ChatGPT Health explains lab values in plain language, helps users identify patterns across lifestyle data such as sleep, activity, and nutrition, and supports patients in framing clearer questions before or after a doctor’s visit. The intent is to complement clinical care by improving comprehension and preparedness, not to replace medical judgement.

Dr Akshat Chadha believes this distinction is critical. “There is a lot of information out there—some right, some wrong, some exaggerated. But even correct information may not be relevant for a particular patient,” he says. “People end up reading things they don’t need, which creates more problems than solutions.”

He sees value in AI tools that streamline relevant information for individual users and present it simply, but draws a firm boundary. “Such tools should stop short of diagnosis—even differential diagnosis—and avoid treatment options or dosage details. Otherwise, self-medication increases.”

That concern is reflected in existing research. A systematic review and meta-analysis titled Prevalence and Predictors of Self-Medication Practices in India: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis, which examined 17 studies involving 10,248 participants, found a pooled self-medication prevalence of 53.57% across Indian populations. While the figure warrants cautious interpretation, its scale underscores why doctors consistently warn against digital and AI-driven tools straying into treatment advice.

Sensitive conditions and delayed care

In specialties such as urology, delayed consultation is already common. Dr Satyajeet P. Pattnaik, urologist and transplant surgeon, says hesitation is often driven by fear, stigma, and informal advice. “Patients delay seeing a doctor due to poor understanding, fear, or guidance from non-medical sources. Many end up self-medicating,” he says.

He sees potential value in AI tools that help patients organise symptoms ahead of a clinic visit. “We are moving into an era of preventive medicine. If patients can articulate symptoms more logically, it allows for earlier detection.”

But he warns against over-reliance. “Misdiagnosis and inappropriate self-medication with over-the-counter products can delay proper treatment.”

Fever, fear, and the problem of self-interpretation

Anxiety around lab reports is not limited to chronic illness. In India, it often peaks during seasonal outbreaks, when families attempt to interpret symptoms themselves and delay medical care.

Dr V. Ramasubramanian, infectious disease specialist at Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, says early misinterpretation becomes especially dangerous in outbreak settings. “During surges, even small delays can lead to complications,” he says. “AI can help patients decide when escalation is needed, but it can only offer opinions—not conclusions. Clinical validation is essential.”

Where he is most cautious is antibiotic misuse. “Many patients still see antibiotics as cure-alls, even for viral infections,” he says, adding that real-world decisions are shaped by cultural beliefs, local epidemiology, and the quality of information entered. “That makes unsupervised AI guidance particularly risky.”

Used carefully, he suggests, AI works best as a preparatory tool—helping patients understand tests and organise questions—rather than as a substitute for medical judgement.

A public hospital lens

From a public healthcare perspective, scale and access remain central challenges. In urban districts, unstructured referral pathways often push patients toward tertiary hospitals even when conditions could be managed at lower levels, leading to congestion and delayed care.

Dr Ranjit Mankeshwar, Associate Dean at the Sir J.J. Group of Hospitals in Mumbai, sees scope for AI-based interpretation tools in improving patient understanding without adding pressure to an already stretched system. “Especially for understanding medication, laboratory investigations, follow-up, and treatment options,” he says.

He argues that digital literacy concerns may be overstated. “Most patients now have access to mobile phones. If explanations are simple and linguistically localised, understanding should not be a barrier.” However, he stresses the need for limits: “Access to physician-level medication data should be restricted to deter self-medication.”

The risk of misinformation

Dr Sunil Mehta, an anesthesiologist with experience across government and charitable hospitals, agrees that AI tools may improve health literacy but warns of unintended consequences. “AI tends to surface the rarest possible diagnosis, even when it doesn’t fit the situation. That makes patients unnecessarily anxious,” he says.

The concern mirrors what doctors already see with online searches. The difference, he adds, will depend on whether AI systems prioritise probability, context, and caution over exhaustive possibilities.

Health literacy as the real outcome

Whether tools like ChatGPT Health can have a positive impact in India will depend not only on their technological sophistication but also on restraint. Establishing clear boundaries, localisation, using simple language, and aligning with medical ethics will decide if these tools become trusted allies or merely contribute to unnecessary noise.